What Does a Neuron Actually Do?!

In numerous previous articles, we discussed ligands binding to receptors and influencing a neuron’s activity. Today let’s delve into how a neuron actually functions and look through an example of a standard activation of a neuron.

The most basic operation of a neuron is to transmit electrochemical signals downstream to other neurons it is connected to. This is known as firing an Action Potential. Each neuron is connected to a large number of upstream and downstream neurons. It receives signals from previous neurons, and if certain conditions are met, it will fire its own action potential down to all its downstream neurons. This “decision” on whether and when to fire an action potential relies on numerous factors, including all the receptor neurochemistry we’ve discussed in the past. The overall pattern of neuronal activity creates the emergent complexity of our thoughts, behaviors, and consciousness.

So let’s talk about how an action potential actually happens!

Diagram of a typical neuron. Pay extra attention to the Dendrites, Soma, and Axon of this neuron. We will be discussing them heavily in this article.This article will go section by section, moving from the dendrites to the soma all the way down to the axon.Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Depolarization#/media/File:1206_The_Neuron.jpgJourney of a Neuron Firing an Action Potential

Synaptic Signals

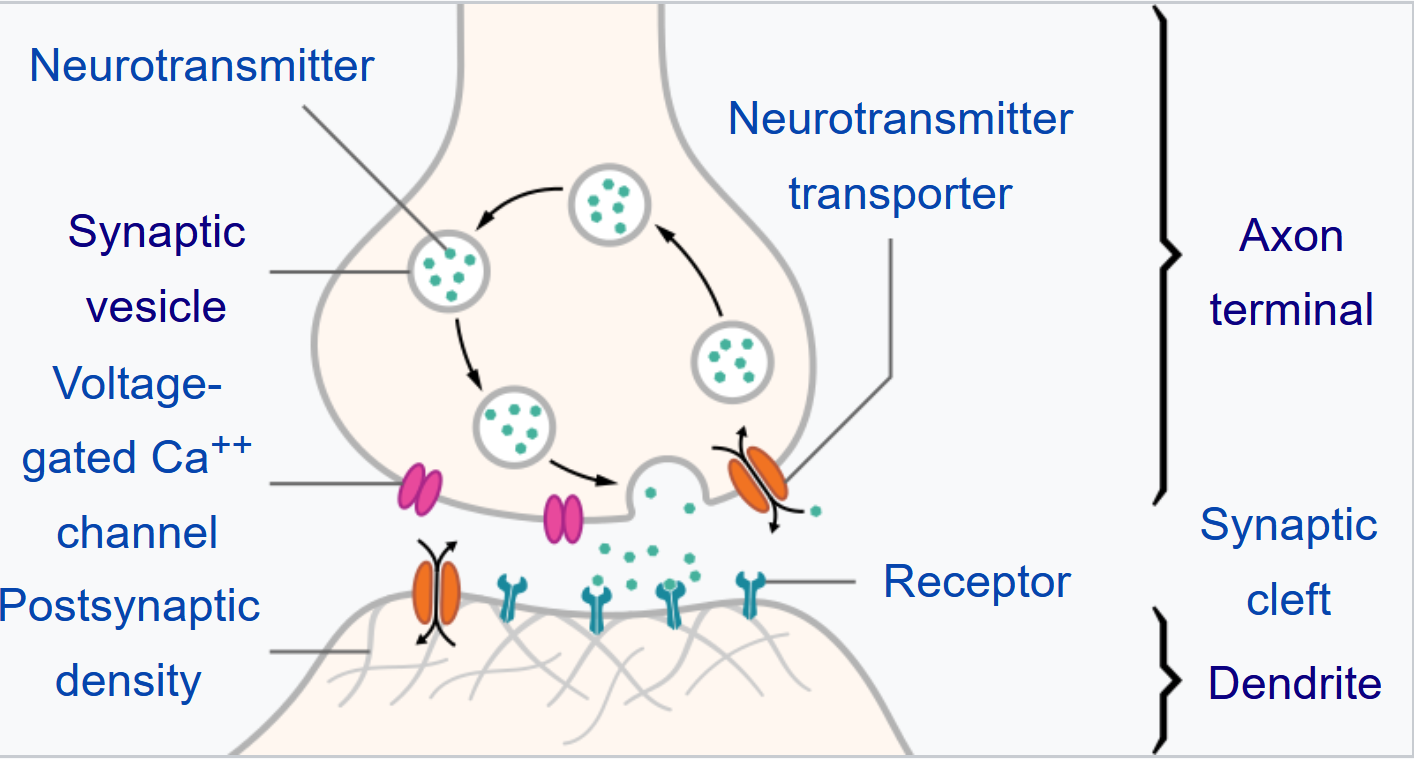

As discussed previously, the connection between two neurons is known as a synapse, and this is where the presynaptic (upstream) neuron transmits signals to the postsynaptic (downstream) neuron via chemical signals known as neurotransmitters. Most articles of this blog so far have explored how different neurotransmitters and drugs can impact the signals being received.

The top shows an axon terminal of a presynaptic neuron, while the bottom shows a dendrite terminal from a post synaptic neuron.

The tiny gap between them in the middle is the synapsePresynaptic Excitatory Signals

In order for a cell to fire an action potential, it needs to receive excitatory signals from the presynaptic neurons. There are numerous excitatory neurotransmitters and their associated receptors, but Glutamate binding to the AMPA receptor is the primary excitatory system for handling fast acting signal propagation.

To explain how glutamate induces an action potential, we must first look at what an action potential is.

Glutamate: The primary excitatory neurotransmitter. Also a signal for umami taste (this is not a coincidence! See the previous article on glutamate for more information)Neuronal Polarization

A neuron is usually in a polarized state, where the overall charge within the neuron is more negative than the charge of the surrounding environment. An action potential occurs during a “depolarization” event, where ion flow has caused the neuron to become more positively charged internally. This change in charge propagates down the neuron and causes several changes to occur, eventually leading to firing a signal to the downstream neuron.

A cell is typically in a slightly negatively charged polarized state.

Depolarization occurs when positive ions enter the neuron and induce a positively charged state

Hyperpolarization occurs when negatively charged ions enter the cell and induce an even more negatively charged state

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Depolarization#/media/File:1221_Action_Potential.jpg Glutamate and AMPA

The AMPA receptor is a highly distributed receptor that is present widely throughout the body. Glutamate is the neurotransmitter that targets the AMPA receptor (amongst other receptors). The AMPA receptor is an ligand-gated ion channel (aka ionotropic receptor), this means that once glutamate binds to the receptor, the receptor opens a channel to allow ions to flow into the neuron.

An activated AMPA receptor is primarily permeable to positively charged Sodium cations. Once glutamate has opened the AMPA channel, numerous Sodium cations enter the cell, causing the local region to become more positively charged.

Dendrite Terminals

Dendrites are long “arms” that reach out from the neuron body, with a dendrite terminal at its end which forms a synapse with an upstream neuron. AMPA receptors are mostly located at the dendrite terminal, waiting to receive glutamate released from the presynaptic neuron.

Once glutamate has activated these AMPA receptors and induced Sodium ions to flow into the neuron, the localized region of that particular dendrite becomes depolarized.

Voltage Gated Sodium Channels

Numerous Voltage Gated Sodium Channels (VGSC) are located along the entire body of the neuron, from the tips of the dendrites through the cell body (soma) all the way down to the tips of the axons.

These VGSCs are typically closed off and inactive, but open up when a certain voltage threshold is reached. A localized depolarization event can cause a sufficient voltage change to open up these channels.

Once these channels are open, they are also selectively permeable to positively charged Sodium ions. This causes the region localized around this VGSC to also depolarize.

This then causes a chain reaction, as the neighboring VGSCs also begin letting in Sodium ions, causing more depolarization. This wave of depolarization -> VGSC activation -> sodium ion inflow -> depolarization continues to propagate down the entire dendrite all the way to the cell body.

Through this, the neuron’s dendrite utilizes chemical and electrical messengers to transmit a signal to the cell body.

A series of VGSCs located next to each other.Each of these will fire one after another, leading to signal propagation down the length of the cell.Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Depolarization#/media/File:1221_Action_Potential.jpg Depolarization Propagation

A neuron typically comes with a large number of dendrites connecting to a large number of presynaptic neurons. Frequently a wave of depolarization from a single dendrite might not be necessarily enough to induce the entire cell to depolarize.

If too few dendrites have depolarized, this wave might simply fizzle out eventually, not leading to an action potential. (These failed signals can lead to the neurons treating it as a mistake and slowly weakening that specific synaptic connection or pruning it completely in a process also controlled by Glutamate but on the NMDA receptor instead. But this is out of scope for this article).

Instead, if enough dendrites have received excitatory signals, the resulting wave of depolarization could potentially induce enough of a voltage change in the cell body that VGSCs can continue propagating the signal forward, firing an action potential

Continued Propagation Down Axons

Dendrites are the input arms of a neuron, while Axons are the output arms. Each neuron is equipped with a single axon that then splits up into numerous axon terminals, each potentially connecting to different neuron.

Once the neuron has depolarized, VGSCs on the axons continue to let in Sodium ions one at a time and propagating the depolarization all the way down to the axon terminals.

Axon is labeled in this diagramAxon Terminals and Voltage Gated Calcium Channels

Once the depolarization have reached the axon terminals, the voltage change now triggers a different type of voltage gated channel known as the Voltage Gated Calcium Channels (VGCC). These work very similarly to VGSCs, but are selectively permeable to positively charged Calcium cations instead of Sodium.

While positively charged calcium cations can also serve to depolarize the neuron, they also have numerous roles within the neuron as a secondary messenger, triggering a variety of cellular processes.

Here, the VGCC is used to signal the release of neurotransmitters. Once the calcium cations enter the axon terminal, they bind to terminal vesicles which store excess neurotransmitters. The calcium ions induces these vesicles to release their stored neurotransmitters into the neuron, where they are eventually transported out of the axon terminal into the synapse.

Here, these released neurotransmitters bind to the receptors on the dendrite terminal of the next cell, starting the process over again, propagating the signal downwards.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:SynapseSchematic_lines.svgRepolarization and Voltage Gated Potassium Channels

After all this occurs, the cell needs to go back to a polarized state to be ready for the next action potential. It achieves this by using a third type of voltage gated channels known as Voltage Gated Potassium Channels (VGPC or VGKC). These channels are located all throughout the cell and open up to allow positively charged Potassium cations to exit the cell, there by making the internal charge more negative again in an event known as “repolarization”.

After all this, there are sodium and potassium pumps that use ATP (cellular energy) to exchange sodium ions for potassium ions in order to replenish its internal store of potassium and deplete its internal store of sodium.

These two processes reset the cell back to the state it was in prior to this action potential. The first step helps to rebalance the electrical charge while the second step helps to rebalance the concentrations of important ion messengers.

Inhibitory Signals and Hyperpolarization

Opposing the excitatory signals are the inhibitory neurotransmitter/receptor systems. Chief among these is the GABA neurotransmitter and the GABA A receptor.

GABA A is also a ligand gated ion channel (ionotropic receptor). However, once GABA binds to the receptor, instead of letting in positively charged ions, it lets in negatively charged Chloride anions. This influx of negatively charged ions makes the neuron become even more negatively charged than usual leading to an event known as “Hyperpolarization”.

A hyperpolarized neuron requires far more positively charged cations than usual to induce a depolarization, thus hyperpolarization serves as an inhibitory signal for a cell. This acts as a “brake pedal” for the neuron, slowing down neurotransmission.

A careful balance between excitatory and inhibitory signals is constantly maintained to enable healthy brain function.

Gamma Amino-Butyric Acid (GABA), the primary inhibitory neurotransmitterOther Factors

We only discussed the simplest and most prevalent excitatory and inhibitory systems in the brain. While these are the most prevalant signaling systems, it does not tell the complete picture. We have dozens of different neurotransmitters and receptor systems that all impart a variety of complex effects. Many of these other systems also cause excitatory or inhibitory signals, contributing to the overall “decision” to fire an action potential. Other receptor systems are more complicated than signaling a simple go vs stop and can induce a variety of complicated intraneuronal processes through secondary messengers.

G-Protein Coupled Receptors and ion-gated Calcium channel receptors all tend to create a variety of complex intracellular effects that cannot be neatly categorized into simply an excitatory or inhibitory message. This process is highly complicated and I know I’ve said many times now that we’ll save it for a future article. Unfortunately that future is not here yet, but I promise one of these days I’ll explain how GPCRs work.

Serotonin Receptor Subtype 2A (5ht2a Receptor), a GPCR that allows different ligands to activate it in a selective manner allowing for complex effects that go far beyond a simple excitatory or inhibitory signal.Specialized ligands selectively activating (biased agonism) the 5ht2a receptor is the primary mechanism behind psychedelic hallucinations.